Overview

Bariatric Surgery

This article aims to provide an overview of bariatric surgery. It aims to define terms and definitions used when discussing bariatric surgery and to highlight the importance of surgery in the treatment of obesity. The main bariatric procedures are discussed highlighting the basic surgical steps involved, the anatomy of the patients after surgery, the risk and benefits of each.

Introduction and Definitions

The prevalence of obesity in the UK is increasing on an annual basis whilst an estimated 1.7 billion people worldwide are classified as obese. For many patients short-term weight loss is achieved with conservative measures (diet, lifestyle, medication) but long-term weight control is harder to maintain. Surgery has been shown to be the most effective and long lasting treatment for weight loss.

Obesity should be considered as a chronic disease associated with a large number of co-morbidities that can be improved or cured as a result of weight loss. These are summarised by organ system in the table below. It is clear that obesity is not simply a weight problem.

| System | Comorbidities |

| Metabolic | Diabetes, dyslipidiaemias |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, Coronary artery disease, DVT, PE, Atherosclerosis (and Stroke), Venous hypertension |

| Pulmonary | Sleep Apnoea, Asthma |

| Gastrointestinal | GORD, Oesophagitis, Hepatic steatosis, NASH, Cirrhosis, and Cholelithiasis |

| Musculoskeletal | Osteoarthritis, Gout, and Carpal tunnel |

| Gynaecological | PCOS, Infertility, Stress related urinary incontinence, Menstrual irregularities |

| Malignancy | Prostate, Colon, Breast and Endometrial Cancers |

| Neurological | Migraine, Depression |

The term metabolic syndrome is often used to describe patients who have a set of medical conditions predisposing to the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Obesity is integral to this. The World Health Organization criteria (1999) defines metabolic syndrome by the presence of one of:

Diabetes mellitus, Impaired glucose tolerance, Impaired fasting glucose or Insulin resistance;

AND two of the following:

Hypertension, Dyslipidemia, Central obesity: waist:hip ratio > 0.90 (male); > 0.85 (female), or body mass index > 30 kg/m2, Microalbuminuria.

BMI= Weight (kg) ™ ÷ (Height (m))2

| Weight Category | Body Mass index (kg/m2) |

| Underweight Below | 18.5 |

| Normal | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| Overweight | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| Obese | > 30 |

| Severely Obese | > 35 |

| Morbidly Obese | > 40 |

| Super Obese | > 50 |

Summary of NICE Guidance

Recommendations for surgery in the UK are based around NICE guidelines, which were published in 2006. The recommendations suggest that the following criteria are fulfilled for all patients considering bariatric surgery. (National Institute of Clinical Guidance, 2006)

- Age > 18

- Have received treatment in a specialist obesity clinic at a hospital

- Have tried all other appropriate non-surgical treatments to loose weight but have not been able to maintain weight loss. Patients with a BMI of >50 do not need to have exhausted conservative measures

- There are no specific medical or psychological reasons why they should not have this type of surgery

- They are generally fit enough to have an anaesthetic and surgery

- They understand the need for follow up by a Doctor and other healthcare professionals such as dieticians and psychologists.

If these conditions are fulfilled then surgery for obesity should be considered for patients with:

- BMI of 40kg/m2

- Or >35kg/m2 with a significant disease (hypertension, sleep apnoea, diabetes) that may be improved with weight loss.

How Does Surgery Compare with Conservative Treatment?

The Swedish Obesity Subjects Study has provided the best evidence that when patients become obese, conservative treatment fails over longer follow up (Sjostrum L, 2007). They conducted a prospective controlled study in 2010 obese participants undergoing surgery who were matched 2037 obese controls undergoing conservative treatment (non-surgical). With conservative treatment already obese patients gained 2% body weight at 10 year follow up compared with 16% weight loss with surgery (mostly vertical gastric banding). Whilst the surgical outcomes are modest compared with more modern procedures it does confirm that non-surgical weight loss management does not work well for patients who are already very overweight. More recent reports suggest that Gastric bypass produces in the region of 60% weight loss at 2-5 year follow up.

Nevertheless lifestyle, dietary and exercise advice is the mainstay of any bariatric intervention and indeed this message needs to be reinforced up to and after any surgical intervention. Patients need to understand that surgery is only part of the solution and without making changes to diet and lifestyle, even the best performed surgery will produce disappointing results.

Slimming clubs and NHS led weight loss classes are available and all obese patients with a BMI less than 50kg/m2 need to have exhausted these options before surgery should be considered. Various medications have been developed with varying effect and side effects. Sibutramine, a serotonin/norepinephrine/dopamine reuptake inhibitor aids weight loss by increasing metabolic rates but a side effect of this is increasing cardiac preload. This has recently been shown to lead to increased risk of cardiovascular events and as such sibutramine has been withdrawn. The other commonly prescribed medication is Orlistat, which inhibits pancreatic lipase activity and hence reduces fat absorption. It has been shown to provide 2-3kg weight loss over a year but resulting soft “fatty” stool and anal leakage limits its long-term use.

The impact of obesity on health

From a public health perspective the co morbities associated with obesity and their treatment are extremely costly, in addition to indirect costs of time of work, unemployment and early death. A recently published paper has reinforced the cost effectiveness of treating obese patients with surgery ((Maklin, 2010). They state ‘bariatric surgery is more cost effective as it increases health related quality of life and reduces the need for further treatment, and total healthcare costs among patients who are very obese”. Over a ten-year period the healthcare costs of treating an obese patient with surgery in Finland will be 33870 Euros compared to 50495 Euros for non-operative care. Perhaps one of the most pressing issues is that bariatric surgery is positive for the economy but only 1-2% of eligible patients are currently undergoing surgery. (Seki K, 2010)

Compared to normal weight patients, obese patients in their twenties have a significantly reduced life expectancy. Obese males have a 13-year reduction in life expectancy compared to non-obese controls and for women the reduction is 8 years.

The aim of weight loss surgery is not simply weight loss but resolution of associated comorbidities. One of the longest studies of RYGB post op follow up has shown resolution or improvement in diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and obstructive sleep apnoea of 83%, 87%, 67%, and 76% respectively at ten years post op. (Higa K, 2011) A further study has confirmed that the early results of SG are slightly less than RYGB but superior to (Hutter MM).

Pre operative Work Up and Decision to Operate

The aims of preoperative work up are to identifying contra indications to surgery and assess fitness for general anaesthesia. Most patients undergo an endocrine screen including thyroid, diabetes and parathyroid tests. Depending on symptoms sleep apnoea studies, upper gastro intestinal endoscopy and pH manometry may also be required.

As with all surgery the decision to intervene is based on assessment of the risks and benefits of the procedure. These vary with each procedure and so the decision to operate requires careful consideration with an emphasis on patient education, with special regard to expectations of weight loss, risks, side effects, and complications of each of the surgical options available. A multidisciplinary approach is required with input from the surgeon, anaesthetist, dietician, specialist nurse and psychologist.

Many centres require patients with a BMI of <50 to demonstrate a commitment to lifestyle and dietary change by meeting a pre operative weight loss target on the basis that this will identify patients who will be able to maintain these changes after surgery. The effectiveness of this step has not been proven (Cassie S, 2011) but it seems reasonable that if a patient gains a significant amount of weight whilst in the run up to surgery whilst following the diet and lifestyle that is necessary for success after surgery, then surgery itself may not be the solution.

The mortality rates for each surgery reflects the complexity and duration of the procedures and patient characteristics. Gastric Banding has a mortality rate of 0.05%, Sleeve gastrectomy 0.1-0.3%, Gastric Bypass 0.5% and upto 1.1% for malabsorptive procedures. The main causes of death are thrombo-embolic events (40%), cardiac complications (25%) followed by anastomotic leak (20%).

How much weight loss will be achieved?

The most readily measured outcome is percentage of excess weight loss (EWL). This is calculated by identifying the ideal body weight from Metropolitan Life Tables and then calculating the excess weight.

The most comprehensive review of bariatric interventions was performed by Buchwald et al and assessed 10,000 patients. (Buchwald H, 2004) Overall EWL% for all surgical interventions was 61% with 47.5% for gastric banding, 62% for gastric bypass and 70% for malabsorbative procedures. Sleeve gastrectomy has grown in popularity since this analysis but has been shown to produce comparable weight loss and have similar impact on metabolic syndromes at early follow up as RYGB. (Bayham BE, 2011) Diabetes remission rates of between 60-80% are expected.

Whilst many surgeons still perform RYGB as a first choice procedure sleeve gastrectomy has been shown to produce results that are superior to LAGB for weight loss and remission of diabetes (Deitel M, 2011) and as such has gromw in popularity over recent years.

The evidence base for the benefits of each of the above procedures is steadily increasing but there is a shortage of randomised controlled trials comparing the different interventions for patients with different co-morbidities. As such the choice of procedure is generally based on surgeons expertise and patient preference. Indeed in the correct setting gastric banding can produce excellent results but more commonly the EWL is less than gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. All 3 commonly performed procedures (LAGB, RYGB and SG) have acceptable efficacy and safety and the choice of procedure should be tailored to the patient (Franco JV, 2011).

A highly motivated patient who enjoys bulk eating, who is active may get very good results with a gastric band. A more elderly patient, with a sweet tooth and a grazing eating pattern suffering with type 2 diabetes and severe osteoarthritis get a better result with a Roux en y gastric bypass. Likewise a super morbidly obese patient may benefit from a staged procedure, starting with a sleeve gastrectomy with progression to a duodenal switch. The results from Roux en y gastric bypass are very reproducible and this is now the most commonly performed procedure in most UK centres. Nevertheless the evidence base for Sleeve gastrectomy is rapidly growing for its application as a primary procedure.

Surgical Options

These can be divided into 2 main categories:

Restrictive Procedures: these act by physically restricting the volume of food that can be ingested. Examples include gastric balloon, gastric band, sleeve gastrectomy and roux en y gastric bypass.

Malabsorbative procedures: these tend to have a restrictive component involving gastric resection and a second malabsorbative component created by bypass large lengths of the small bowel. Examples include duodenal switch and biliopancreatic diversion

Whilst a Roux en Y Gastric bypass does involve bypassing a segment of small bowel the weight loss effects are now thought to relate largely to the restrictive effect of creating a small gastric pouch and so should be thought of as a restrictive procedure.

Restrictive Procedures:

Gastric Balloon: This is the least invasive of procedures and is performed in the endoscopy unit. The patient swallows a deflated 600ml balloon and once position in the stomach has been confirmed by endoscopy the balloon is inflated. The effect is to create a sensation of early satiety and hence a reduction in calorie intake. The effects are dependant on patient compliance. The balloon is often a useful first line procedure when dealing with super morbidly obese patients to reduce their BMI and hence operative risk prior to more definitive surgery. The balloon remains in situ for up to 6 months before needing removal, once again by endoscopy.

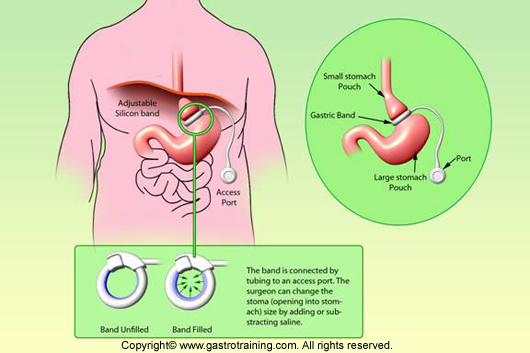

Gastric Band: the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band has largely replaced the early vertical banded gastroplasty although complications of these may well present as emergencies and an understanding of the anatomy is important if surgery is required in this setting. (IMAGE)

LAGB: At laparoscopy a tunnel is created around the upper stomach by opening the pars flaccida on the lesser curve and tunnelling through a small cut in the peritoneum anterior to the right crus, behind the stomach and up to the angle of his at the gastro oesophageal junction. The band is then pulled through this tunnel and closed around the stomach creating a small gastric pouch above the band. The band can then be secured in position with a few stitches. The tightness of the channel through the band can be adjusted by injecting fluid into the band through a port, which is positioned in the subcutaneous tissue on the fascia of the anterior abdominal wall and connected to the band via a plastic tube.

The weight loss effect is purely restrictive and again patient compliance with suitable diet is essential. High calorie sugary foods like ice cream will easily pass through the band, whereas bread can often get stuck resulting in severe vomiting. Adjustment of the band is necessary to get the correct level of restriction. Over tightening of the band can resulting in slippage of the band, pouching (enlargement of the pouch above the stomach) (10%) and may lead to band erosion through the gastric wall (1%). Under tightening will result in poor restriction and as a result poor weight loss. Band adjustments are often performed under X ray guidance initially.

Major intra and postoperative complications are rare but port site problems (infection, flipping) and band or tubing malfunction are more common with up to 15% of patients requiring re operation. GORD can be exacerbated by the band and many surgeons will investigate for this before surgery with upper GI endoscopy or pH manometry. If a small hiatus hernia is identified this can be repaired at the time of surgery by opposing the crura with a couple of well-placed sutures. Significant reflux is a relative contra-indication.

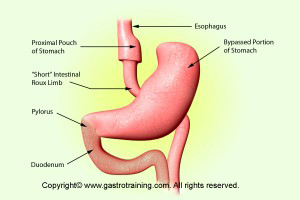

Roux en y gastric bypass

This has become the most commonly performed procedure in most bariatric centres across the country.

Initial weight loss is often rapid with a 60% EWL at two years. Many patients experience later weight gain of around 10% of weight lost. This is commonly due to dilation of the alimentary limb and pouch and may be treated by adding a restrictive band around the alimentary limb. This known as a banded bypass.

The procedure can be divided into several separate steps.

After initial laparoscopy and insertion of a liver retractor dissection begins at the angle of his followed by dissection at the lesser curve of the stomach to enable insertion of a stapling device. After one firing across the stomach the angle of firing is changed, with progression up towards the angle of his. This will create a small (30ml) gastric pouch and a gastric remnant.

At this point small bowel is measured distally from the angle of trietz and divided. The distal limb is delivered up to the stomach and anastomosed creating the alimentary limb. The proximal end (the biliary limb) is then anastomosed 150cm from the gastro jejunostomy to create a common channel distally.

The techniques used vary between linear and circular stapling and hand sewing, additionally the alimentary limb can be delivered to the stomach over the transverse colon (anti colic, requiring division of the omentum) or through the transverse mesocolon (retro colic). The lengths of the limbs are also subject to variation and the effects of increasing the limb lengths are not fully established.

The net result is a combination of restriction (small gastric pouch) and a small malabsorbative effect (proximal small bowel bypassed) but undoubtedly there is an endocrine effect as evidenced by the rapid correction of insulin resistance after the procedure. In addition patients who eat sugary foods after this procedure of develop dumping syndrome causing unpleasant side effects and acting as a deterrent to eating certain food types.

Internal hernia can form behind the alimentary limb or in the mesenteric defects and this can cause intestinal obstruction necessitating emergency surgery. Internal hernia rates of 16% at 10years have been reported(Higa K, 2011). This has lead many surgeons to close these spaces at the time of surgery but the effectiveness of this time consuming step has not been proven,

Post operatively patients are commenced of multivitamin tablets, cholecystyramine to reduce gallstone formation, calcium supplements and B12 injections. Regular monitoring of weight and nutritional status is requiring during long term follow up.

Mortality rates are 0.5% but post complications can be very serious. It is worth noting that the mortality rate of RYGB is similar to that commonly quoted of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Postoperative bleeding and anastomotic leaks occur in up to 5%, whilst stenosis of the anastmoses occur in around 5%. Long term nutritional follow up is essential to detect and treat nutritional, vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Sleeve gastrectomy

The role of sleeve gastrectomy is evolving, once thought only to be suitable as the first part of a staged approach with progression to a malabsorbative procedure as necessary, the excellent results have meant this is now being used as an alternative to gastric band or bypass. This is the procedure of choice in the presence of hepatomegaly/ cirrhosis or intrabdominal adhesions, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease and gastric/duodenal polyps (for which surveillance of the gastric remnant after a bypass would not be possible). Expert consensus suggests this is also the procedure of choice when converting from a failed or complicated gastric band. (Rosenthal RJ, 2012) GORD is a relative contraindication to this procedure with many (12%) patients reporting an exacerbation of reflux symptoms post operatively. The literature is not clear whether a hiatus hernia is an absolute contraindication.

The procedure involves linear stapling of the stomach starting approximately 6cm from the pylorus and extending upto the GOJ along the lesser curve of the stomach. A large orophayngeal tube is inserted down the lesser curvature of the stomach to act as a guide to prevent over narrowing or laxity in the sleeve that remains. A narrow sleeve is under higher pressure and has an increased leak rate whilst a lax sleeve provides less restriction. A size 32-36 Fr bougie is recommended to size the sleeve correctly. After division of the short gastric vessels the remaining portion of the stomach is removed. The result is a long narrow sleeve with a 60-200ml capacity.

Whilst largely restrictive the metabolic, weight loss and appetite suppressive effects are greater than may be expected from this effect alone. The additional effects have been attributed to removing the fundus and hence the effect of ghrelin which is produced primarily in the fundus and is an appetite stimulating hormone.

Postoperative bleeding form the staple line is the most commonly seen early complication whilst structuring or dilatation of the sleeve sometimes necessitate re do surgery. Bleeding and leak rates are reported at 1-3% with a mortality rate of 0.1-0.3%

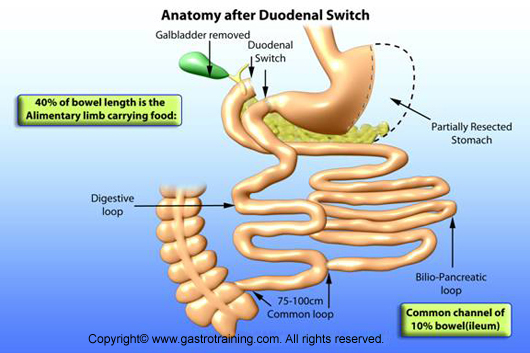

Duodenal Switch

This is regarded as the most effective procedure in terms of weight loss but is associated with concerns over longer-term nutritional deficiencies and postoperative diarrhoea in addition to prolonged operating times. The procedure is most commonly performed on super obese patients and this may explain why postoperative complications are higher.

The procedure involves the first step of performing a sleeve gastrectomy followed by division of the first part of the duodenum. The terminal ileum and ileocaecal valve is the identified and the terminal ileum measured proximally. At 250cm form the ileocaecal valve the ileum is divided and the distal end is delivered to the upper abdomen in an ante colic or retro colic manner and anastomosed to the distal end of the stomach at the first part of the duodenum to create the alimentary limb. The remaining limb of small bowel is the biliary limb and this is then anastomosed to the terminal ileum 100cm from the ileocaecal valve. This 100cm is the common channel where both food and biliary/pancreatic juices are present.

By preserving the pylorus dumping syndrome commonly seen after Roux en Y gastric bypass is avoided.

Biliopancreatic bypass

This is very similar to the duodenal switch but the stomach is divided in its upper third and horizontally and the alimentary limb anastomosed at this point. The pylorus is therefore excluded but remains in position with the remaining gastric remnant.

Pros and Cons of Each Procedure

| Procedure | Pros | Cons |

| Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band | Lowest Risk Procedure

Reversible Least Demanding Procedure Excellent and established safety profile |

Success very dependant on patient factors.

Less weight loss compared to other procedures Need for band fills Port and band complications Risks of slippage, pouching and erosion |

| Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy | Favorable safety profile

Excellent weight loss High diabetes remission rates No dumping syndrome No need for dietary supplementation Conversion to bypass possible |

Long staple line: bleeding/leak rates

GORD is a relative contraindication Long term results less clear Risk of stricturing or dilation requiring revisional surgery Irreversible |

| Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass | “Gold standard procedure”

Excellent weight loss High diabetes remission rates Low complication rates |

Technically more demanding than sleeve/band

Long term nutritional supplements Dumping syndrome Internal Herniation Irreversible ERCP not possible Gastric remnant surveillance not possible with gastric polyps Risk in Crohn’s disease Not possible with extensive adhesions |

| Duodenal Switch/ BPD | Most Dramatic weight loss

Highest diabetes remission rates |

Long term nutritional deficits

Diarrhoea/flatus Very demanding surgery |

Endoscopic Treatments for Obesity.

Given the success of surgical intervention for obesity the search for effective endoscopic or less invasive treatments is progressing. As mentioned above gastric ballooning has a small weight loss effect but new technologies are developing quickly. These can be divided into groups depending on their intended mechanism of action

- Gastric Restriction: Intended to reduce the capacity of the stomach and induce early satiety. E.g. Gastric balloon, endoscopic gastric plication

- Malabsorption: aimed at creating a barrier between food and the intestinal wall and biliopancreatic secretions: e.g. duodenal-jejunal sleeve

- Neurohormonal: Neuromodulators are currently being developed to reduce satiety and food intake by neurohormonal actions, usually involving modulation of the vagus nerve and it’s signaling to the brain. E.g. Tantalus system,VBLOC

Currently the weight loss effects are less than the results seen with surgery but the role of these procedures in treating patients with less severe obesity (BMI 30-35) or as bridge treatment (risk reducing) step prior to surgery is under development.

The Future

The current trends in bariatric surgery are changing rapidly as understanding of the metabolic and endocrine factors involved in obesity is being understood. The ultimate aim is to develop a procedure that is safe, reproducible, durable and effective in causing weight loss with out malabsorbtion side effects that cures insulin resistance and other elements of metabolic syndrome. Some surgeons would argue that Gastric bypass is not far of this.

Single incision surgery and natural orifice approaches may become more popular but are currently not used in widespread practice and have not been subject to randomised trials (CK, 2011) Interest in endoscopic approaches (e.g. endo barrier) is also growing. Perhaps with increased understanding medical therapy will provide an effective alternative.

Regardless of the methods and techniques the importance of treating obesity and associated conditions must not be underestimated. There are not many other interventions that can boast an 89% relative risk reduction of death, which has been reported following gastric bypass surgery (Christou NV, 2004).

The arguemnet that prevention is better than cure is very strong but the obesity epidemic is a current day problem for which surgery has been shown to be an effective cure. Obese adolescents have a high probability of progressing into adult life with severe obesity and diet and lifestyle interventions may not be enough for some of these patients. The role of surgery in chiildren is a highly contentious issue and has not been accepted in this country.

Works Cited

Bayham BE, G. F. (2011, Sep). Early Resolution of Type 2 diabetes seen after roux-en-y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Diabetes Technol Ther.

Buchwald H, A. Y. (2004). Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA , 292, 1724-1737.

Cassie S, M. C. (2011). Effect of preoperative weight loss in bariatric surgical patients: a systematic review. Surgery for Obesity & Related Diseases, 7 (6), 760-7.

Christou NV, S. J. (2004). Surgery Decreases long-term mortality, morbidity and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg , 240, 416-423,423-424.

CK, H. (2011). Sinlge incision laparoscopic surgery. Journal of Minimal Access Surgery , 7 (1), 99-103.

Deitel M, G. M. (2011). Third International Summit: Current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases , 7 (6), 749-59.

Franco JV, R. P. (2011). A review of studies comparing three laparoscopic procedures in Bariatric surgery: sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric banding. Obesity Surgery , 21 (9), 1458-58.

Higa K, H. T. (2011). Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. . Surgery for Obesity & Related Diseases, , 7 (4), 516-525.

Hutter MM, S. B. First Report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Centre Network: Laparoscopic sleeve gasrtrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness postioned between band and bypass. Ann Surg , 254, 410-20.

L, S. (2008). Bariatric Surgery and Reduction in Morbidity and Mortality: experiences from the SOS study. International Journal of Obesity , 32 (suppl 7/(s93-7)).

Maklin, e. a. (2010). Cost-Utility of Bariatric Surgery for Morbid Obesity in Finland. British Journal of Surgery , 98.

NICE. (2006). NICE Clinical Guideline 43.

Rosenthal RJ, e. a. (2012). International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of 12,000 cases. Surg Obes relat Dis , 8 (1), 8-19.

Seki K, K. K. (2010). Current Status of laparoscopic bariatirc surgery. Surgical Technology International , 20, 139-44.

Sjostrum L, N. K. (2007). Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Mortality in Swedish Obese subjects. New England Journal of Medicine , 357 (8), 741-52.

Contributed by: Mr Will Carr

Editor: Mr Jeremy Cundall